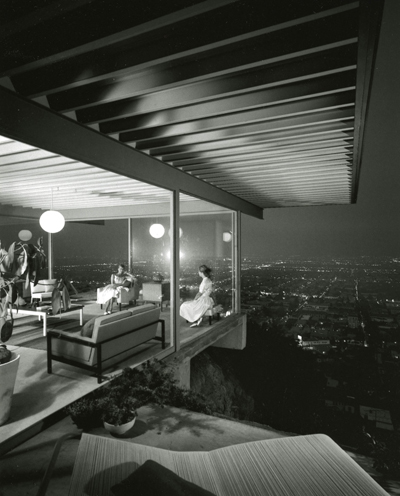

Julius Shulman’s “Case Study House #22, Los Angeles, 1960”

“Therein reign order and beauty, luxury, calm and voluptuousness”

Charles Beaudelaire, L’Invitation au Voyage

Julius Shulman’s shot of CSH #22, a house of glass and steel built by architect Pierre Koenig, exudes a sense of quiet comfort and happiness. The composition is divided in two. The foreground is part of a room in this mid-century modern Southern California home, seen from the outside through floor-to-ceiling windows.The background is an urban nightscape, with rectangular city blocks. The distance between foreground and background is so great that they appear unconnected. The privileged, brightly lit dwelling seems to float in the sky above the uninvitingly dark, flat city receding into the distance. The resulting impression is consistent with the optimism of western architecture at the time, promoting a piece of the American dream for all.

There are no men in the picture; only two women dressed in white. The one that occupies the precise geometrical center of the photograph is not in the center of the apartment: she is sitting straight-backed on an ottoman in a corner of the room, facing the other woman who is reclining in an armchair in a much more relaxed posture. Perhaps this is a mother and a daughter, or a mentor and a protégée tête-à-tête. According to Shulman, they were the girlfriends of two young architects who worked as Koenig’s assistants1.

The perfect architecture is reflected in the technique of the photographer. The perspective lines – the ones emerging from the house – including the successive reflections of the white ceiling lamp, as well as those from the street-lit city blocks on the ground, all converge in the only empty spot of the composition: over the horizon in the upper right quadrant.

The final element of the composition, almost unnoticed at first, is a white sun-bed, precariously close to the edge of a terrace, suggesting a hint of impending danger.

The feeling of voluptuous beauty appears rather fragile with hindsight, as if the darkness of the real world could eventually bring down the lofty, ephemeral structure. Even more than Baudelaire’s Invitation to Travel, what comes to mind is Jacques Tati’s Monsieur Hulot in his struggle with a very similar kind of modernity. One cannot help but think (and, somehow wish) that outside of the frame of this perfect shot of a perfect home, in the fully robotized kitchen, the electric can-opener is wrecking havoc.![]()

________________________________________

1 http://www.getty.edu/art/exhibitions/shulman/shulman_audio_CSH22.html